Peter Quantrill examines the Decca legacy of the British conductor, responsible for one of the first complete Sibelius symphony cycles to be recorded.

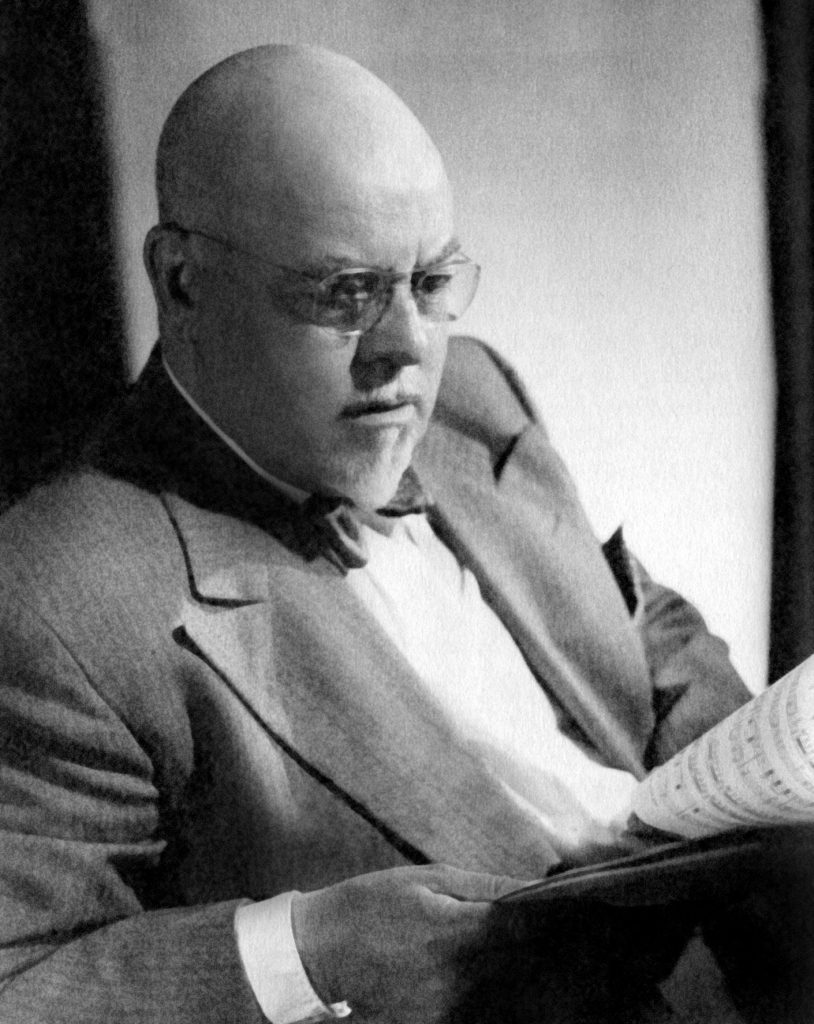

Anthony Collins

PHOTO: TULLY POTTER COLLECTION

Violinists have often left the leader’s chair and stepped on to the podium. Sir John Barbirolli and Arturo Toscanini number among the most distinguished cellists who swapped bows for batons. A rarer beast is the violist turned conductor, though Carlo Maria Giulini studied Toscanini at close hand as a violist in Rome’s Augusteo Orchestra, and composers from Mozart onwards have learnt about string textures from playing in the middle of them. Another distinguished but often overlooked example was Anthony Collins.

Born on 3 September 1893 in the Sussex seaside resort of Hastings, Collins joined the viola section of the town’s Municipal Orchestra at the age of seventeen. Like many similar ensembles dotted along the coasts of Europe – the most noted example in England being the band at Scarborough in North Yorkshire – the orchestra sustained itself with a repertoire of mostly light classics, arrangements and newly composed songs, marches and dances to entertain an audience of both ordinary townsfolk and holiday-makers.

Collins served in the Army during World War I and in 1920 he joined the Royal College of Music in London as a mature student, where his teachers were Achille Rivarde (violin) and Gustav Holst (composition). By March 1924 he was appearing in the BBC’s broadcast schedules as principal violist of the Scottish Orchestra (forerunner to the Royal Scottish National Orchestra), giving a solo recital of Beethoven’s F major Romance and an arrangement of an Irish air. In June the same year he returned to the RCM to conduct the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra (NQHO), founded by Sir Henry Wood, in his own Suite Divertissement.

From the earliest days of his career, then, Collins earned a reputation as a musician of parts: performer, conductor, arranger, composer. In 1930 the RCM staged Catherine Parr, a one-act lyric comedy – ‘a charming trifle’ according to The Times – in which King Henry and his latest wife bicker over the boiling of an egg, previous consorts having apparently done a better job. By then, Collins had left the Scottish Orchestra to become principal violist of the London Symphony Orchestra, playing nightly under the likes of Thomas Beecham and Willem Mengelberg.

The early 1930s were a time of flux for London’s orchestral scene, with both the BBC and Beecham attempting to raise standards (and publicity) through the establishment of their own ventures as rivals to the LSO and NQHO. When Collins took the part of Sancho Panza in Strauss’s Don Quixote under Beecham’s baton one evening in October 1931, the critic for The Times was pleased to make a general note that ‘there had been ample and careful preparation, and there were only one or two smudgy passages in the playing’ (though he was less taken with Strauss’s tone-poem itself: ‘there is too little variety between some of the episodes … some of it is downright dull’).

Then as now, the LSO pursued a hectic schedule, but Collins still found time for composing, and in January 1935 he appeared in the morning series of ‘smoking concerts’ at the Princes Galleries, playing in the premiere of his own Quartet for violin, viola, flute and harp, ‘admirably suited to this type of concert’ (The Times). The White Rock Pavilion had opened its doors in his home town in 1927, and its success was consolidated with an annual music festival in which Collins took an active role. He resigned from the LSO in 1936 and determined to give up playing and go freelance. In 1937 he substituted for Julius Harrison, the resident conductor of the Municipal Orchestra, accompanying Solomon in Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto and, more significantly for his legacy, conducting a small but tantalisingly unidentified piece of Sibelius. It was noted by The Times, however, that Collins ‘showed a real ability to conduct in one who is best known as an eminent viola player’.

The contents of this box celebrate the achievements of Collins as a conductor, and yet, from just sixteen years after that concert in Hastings, he gave an LSO concert featuring the first performance of a Violin Concerto he had written in 1949 for the soloist Louis Kaufman: ‘the overall impression was of “atmospheric” music,’ reported Joan Chissell in the Musical Times, ‘as indeed, might be expected from such a distinguished, experienced film-composer’. Comparisons with Leonard Bernstein, born a quarter of a century after Collins, may seem far-fetched, but music-lovers of the mid-twentieth century knew him as a figure of protean accomplishments by no means confined to the podium.

By 1953, in any case, Collins had found Hollywood, or Hollywood had found him, through the agency of the English film producer Herbert Wilcox. Rewind to the mid-1930s, and Wilcox had sunk his life savings into The Great Victoria, a vehicle for his third wife Anna Neagle (who herself invested £10,000). Collins was hired to write the score, and on its release in 1937 the film exceeded all expectations at the box office. Wilcox secured a ten-year deal with the film distributor RKO Pictures, and a sequel was quickly commissioned: Sixty Glorious Years (1938), also featuring a soundtrack by Collins. The following year he escaped the gathering clouds of war and emigrated to the US as a house composer/conductor for RKO. Collins received an Oscar nomination in 1939 for the score of Nurse Edith Cavell (1939), also starring Neagle and directed by Wilcox, and a string of hits followed: Swiss Family Robinson (1940), Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1940), Destroyer (1943) and Forever and a Day (1943). Collins’s name was now made, first and foremost as a film composer.

Before he left for the US, however, Collins had established himself as a concert conductor, especially through a relationship with his old orchestra, the LSO. He led them in concert for the first time in January 1938: a program of Brahms, Elgar and the ‘Coronation’ Piano Concerto by Mozart, with Wanda Landowska as soloist. ‘The performances he gave should establish him among our leading conductors forthwith,’ declared The Times, and analysed Collins’s style in terms that become leitmotifs in critical reception of his conducting, identifying traits quite recognisable in these Decca recordings: an absence of mannerism and a direct, forthright mode of expression. ‘His reading of Elgar’s [First] Symphony was one of the most poetical we remember; he plunged his audience into its great flood of sound, and without ever coming near to drowning us – he is sparing of dynamic climaxes – he bore us along on its tide to the great waters of its fulfilment.’

In 1939 he founded the London Mozart Orchestra and gave concerts of Classical-era repertoire with them at the Cambridge Theatre – including a Mozart piano concerto with the solo part played by William Glock, who went on to have a transformative effect on British musical life as the founder of the Dartington Festival and Controller of the BBC Third Programme and the Proms. At the end of the war Collins returned to the UK, and immediately struck up a partnership with Decca that yielded the recordings in this set.

Not all artists enjoy a career in the studio that represents them fairly, and the Collins discography is a slender one, but Decca played to his strengths. They began working together in May 1945 with Mozart, and the London Mozart Players: a beautifully turned account of the B flat Symphony KV 319 receiving here its first release since the original 78s were issued in July 1949. As so often, the critic Lionel Salter hit the spot in his Gramophone review: ‘When we lost Anthony Collins to Hollywood, we lost a first-rate Mozart conductor: such can be seen even from this one issue, which is full of felicities of phrasing and dynamics’.

Collins, however, maintained houses and clients on both sides of the Atlantic. There were more Wilcox/Neagle films to be scored, including a wartime romance, Piccadilly Incident (1946), and a Florence Nightingale biopic, The Lady with a Lamp (1951). Five years elapsed before Collins returned to the Decca studios in February 1950 with a Spanish-themed programme of Bizet and Falla, then again two months later for a 33rpm record of ballet music from operas by Humperdinck and Richard Strauss – all repertoire requiring the attention to orchestral colour and fleet-footed rhythms that were hallmarks of Collins’ own film scores.

Anthony Collins’s 1950 recording of suites from Bizet’s Carmen and Falla’s El amor brujo were originally coupled with Bizet’s L’Arlésienne Suite and Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances (Eduard van Beinum), respectively

The Decca producer for these sessions was Victor Olof, who grasped the conductor’s special affinity with the music of Sibelius and was impressed to learn that he had spent years studying the scores. With hopes of making a complete cycle on record – which had not been achieved in the three decades since Sibelius signed off the Seventh in 1924 and at length burned whatever he had composed of the Eighth – Olof engaged Collins to record the First Symphony with the LSO in October 1952. During their preliminary musical discussions, producer and conductor agreed to contact the composer to elucidate some ambiguous metronome markings. Olof sent a lengthy telegram to Sibelius at his home in Finland detailing all their queries, and received an immediate reply: ‘Pleased to hear about recording stop metronome markings difficult to follow strictly stop conductor must have liberty to get performance living greeting Jean Sibelius’. While Beecham and Rosa Newmarch had done much to advance Sibelius’s cause in the UK, and the critic Olin Downes in the US, all of them motivated by an agenda to promote a tonal, northern-European musical language under siege from a modernism they deplored, it was the Collins cycle that established this music in the ears of many listeners outside Scandinavian and Nordic countries.

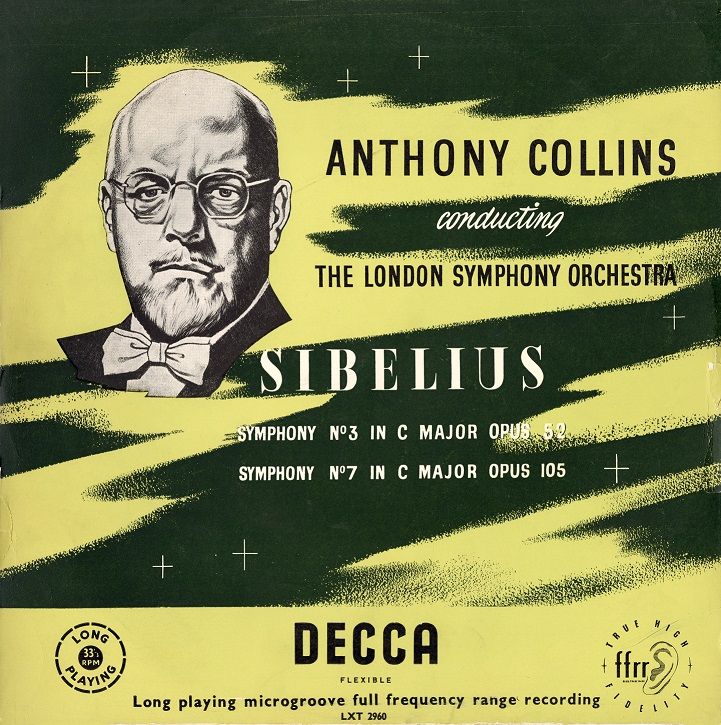

A sketch of Anthony Collins, incorporated into the LP covers of some of his Sibelius recordings

IMAGE: DECCA

The cycle’s artistic and commercial success – the release of the First soon prompted requests for the Second, and the cycle was completed with the Fifth in January 1955 – could be attributed to various factors beyond the conductor’s striking physiognomic resemblance to the composer: Decca’s ‘full frequency range recording’ technique, for one, which captured the composer’s unique brass and timpani writing with an immediacy and a dynamic range unrivalled at the time. Collins also had a notable grasp of Sibelius’s complex metrical structures and fluctuating, accumulative tempo schemes, particularly tested by the episodic narrative of the First and the continual ebb and flow of the Seventh. Not to be overlooked, however, is the degree to which Collins understood his fellow musicians, and they him. Collins knew from within how an orchestra thinks and how a score works, how to draw out the inner parts without spotlighting them – and he knew how to get the most out of a three-hour studio session thanks to his experience with film.

While the Decca cycle was regularly cited as a reference point for decades thereafter, not everyone was delighted by its success: Louis Kaufman, for one, who complained that Collins was too busy with Sibelius to get round to recording his Violin Concerto, the one damned with faint praise by Chissell. Kaufman esteemed it in the same breath as concertos by other Hollywood-influenced composers such as Korngold and Rozsa; he claimed that Collins had been inspired by William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience but had elected to conceal the subtext for fear of critical censure. For his own part, the degree of mutual sympathy between Collins and Beecham and other Sibelius champions may be deduced from the program note he wrote for his concerto: he was ‘tired of the modern composer’s habitual treatment of a solo violin as if it were a hack-saw’; he aimed instead at lyricism for the soloist, whom he envisaged as ‘the prima ballerina at the head of her corps de ballet’.

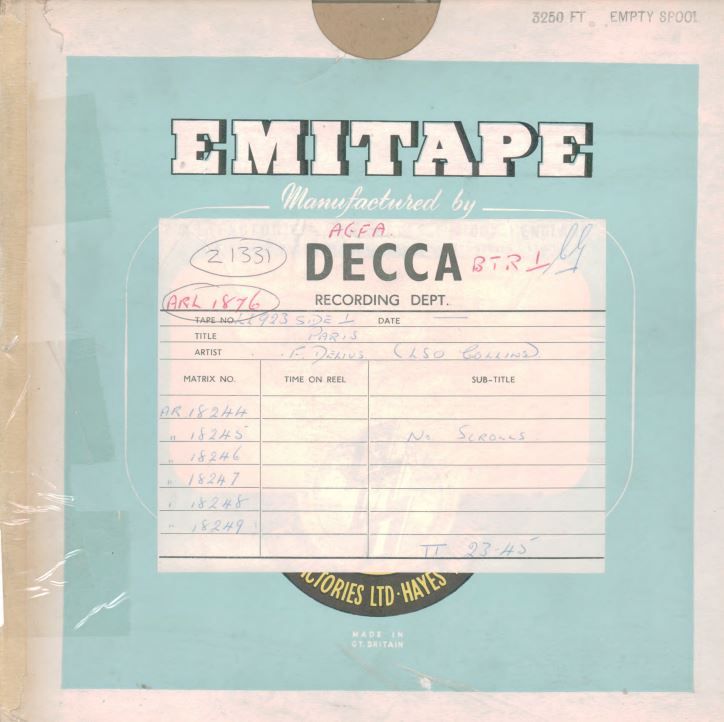

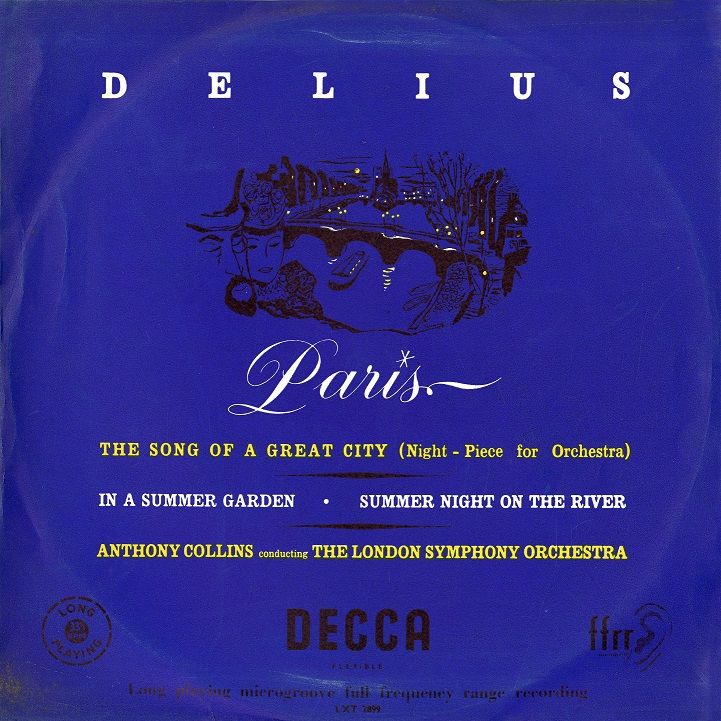

The original tape box and LP cover for Anthony Collins’s Delius recording of Delius’s Paris – The Song of a Great City for Decca in October 1953

Perhaps posterity will rediscover Collins’s own compositions, such as the concerto and a pair of symphonies as well as several stage works. The conductor himself set down only a pair of his light orchestral works in June 1954 for a single 78rpm record: Vanity Fair, a delicately scored orchestral fantasy, and the more rumbustious With Emma to Town. In between Sibelius sessions, however, Collins and the LSO made several other records of English music which have worn equally well. Olof reported that the album of English string music made such a stir in the US that Decca’s US dealer was asked to produce a complete set of the Vaughan Williams symphonies. The commission went to Boult, but Collins did impress the American audience with his two albums of Delius: ‘that composer’s most distinguished interpreter after Beecham’, according to Billboard magazine in 1954, and while the comparisons with the older conductor were inevitable, they did not always incline in Beecham’s favour. The Record Review of 1955 reported that Paris was ‘a flawless achievement’ and in general the combination of Collins’s restraint and Decca’s sound was regarded as letting a measure of light and clarity into scores of sometimes suffocatingly Wagnerian richness.

In the summer of 1954 Collins returned to Mozart: wind concertos and Friedrich Gulda in Mozart’s E flat Concerto KV 449, last of the trio with string-only accompaniment. In November the same year he conducted more Mozart, the Sinfonia Concertante KV 364, at the Royal Festival Hall, and the review by Denis Stevens in the Musical Times highlighted the conductor’s gifts as an accompanist: ‘Mozart’s seemingly innocent score demands incredible co-operation between the two soloists, as well as between the duo and the orchestra, and in this performance the demands were entirely satisfied. Collins should be heard more often, for he has an enviable depth of musical perception, and is equally at home in rococo and romantic, and in classical and contemporary fields.’

What the Decca recordings miss is a sense of Collins’s incisive musical mind in standard symphonic repertoire, such as the Beethoven works he conducted in a seven-concert series with the LSO in the spring of 1955: a ‘rhythmically buoyant’ Eighth Symphony according to The Times, ‘imaginative, yet never inflated’ – Collins as an interpreter in a nutshell. But aside from playing second fiddle to soloists such as Gulda, Lympany, Katin and Ricci, he completed the Sibelius cycle and then made only one more full-orchestral disc, of Tchaikovsky’s Capriccio Italien and Francesca da Rimini at a lower level of interpretative intensity. A ten-inch disc of British light-orchestral music comprised a modest coda to his Decca career, and in February 1957 Collins left the UK to take temporary charge of the Cape Town Municipal Orchestra. Thereafter he retired to his home in Los Angeles for good, and died there in December 1963.

Discover the 14-CD Limited Edition box set HERE