The once-mighty Franco-Belgian school of violin playing suffered something of a thin time in the post-war years. In Belgium, Alfred Dubois died in 1949, aged only 50, leaving his pupil Arthur Grumiaux on a lonely eminence. In France, air crashes claimed Ginette Neveu in 1949, aged 30, and Jacques Thibaud in 1953, aged 72. Fine players such as Henri Merckel, René Benedetti, Devy Erlih, Janine Andrade and Michele Auclair made excellent careers but did not break through to international stardom. It was left to the old master Zino Francescatti and the young hopeful Christian Ferras to carve up the world between them. Francescatti was enormously popular in America, while Ferras ruled over Europe, but of course they ventured into each other’s fiefdoms.

Ferras’s career was so dazzling in the 1950s and 1960s that he seemed to have the world at his feet, yet it was interrupted several times by the illness which led him to take his own life when he was not yet 50. Like Neveu he had a lustrous tone and he left a goodly legacy of recordings, both studio and live. Born in Le Touquet on 17 June 1933, at seven he began violin lessons with his father Léon, a hotelier and a good amateur fiddler who had studied with Marcel Chailley. ‘It was in 1940, at the beginning of the war,’ Ferras later recalled. ‘We were living in Nice. I was ill! My father, a violinist, went into the street. He saw an antique shop. He noticed a little violin there. “Perhaps for Christian,” he thought – and why not? He brought it home. “You want to play it?” he asked. I took it, I started to play, and my father became my first teacher.’

A year later he began studying at the Nice Conservatoire with Charles Bistesi, solo violinist at the local Opéra and a César Thomson pupil. To enter the Conservatoire he had to play a Bériot concerto, which he memorised in a week. In 1942 he made his debut with the Nice orchestra and in May 1943 he was awarded a first prize in violin. A year later he graduated, his performance of Saint-Saëns’s Third Concerto winning him the Premier Prix d’excellence. In October 1944 he went to the Paris Conservatoire, where his teachers were René Benedetti for violin and Joseph Calvet for chamber music; in 1946 he took first prizes in both disciplines. That year he made his Paris debut with the Orchestre Pasdeloup under Albert Wolff, playing Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole (four movements only) and following it up a week later with the Beethoven Concerto.

In 1947 he encountered the Romanian violinist and composer George Enescu, who became his mentor. ‘I consider myself, in principle, as his pupil,’ Ferras wrote, ‘although my technical training had been with other teachers.’ He also had lessons with the Russian emigré Boris Kamensky. On 4 November that year he made his first London appearance at the Methodist Central Hall, with Gaston Poulet conducting the London Symphony Orchestra: he played Mozart’s ‘Turkish’ Concerto and the Elizalde Concerto, which he and Poulet had previously introduced in Paris. On the 7th they took the Elizalde into the Decca Studios. Ferras also played Bach’s Double Concerto with his fellow Enescu devotee Yehudi Menuhin – members of the orchestra were amused that the lad had to stand on a platform to bring himself up to the diminutive Menuhin’s height.

In 1948 he shared first prize in the Scheveningen contest with Michel Schwalbé and the following year he took second prize in the Marguerite Long-Jacques Thibaud competition in Paris (no first prize was awarded). Pianist Pierre Barbizet (1922–1990) was also a competitor and they established an immediate rapport despite the eleven-year age gap. Soon afterwards they began their joint recitals, making up a duo famed not only for the Franco-Belgian repertoire but for Beethoven, Brahms and Schumann. They first appeared in London on 11 October 1951, playing both of Fauré’s Sonatas at the Wigmore Hall. ‘M. Ferras’s voluptuous violin tone and the dashing brilliance of M. Barbizet’s piano-playing were persuasively eloquent,’ The Times reported. The duo eventually followed Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin in playing their sonata repertoire by heart, committing more than 40 works to memory, although for a composer such as Bartók they still resorted to the printed music.

Ferras was back in Britain in July 1954, to premiere Peter Racine Fricker’s Rapsodia Concertante at the Cheltenham Festival on the 15th, with John Pritchard conducting the Hallé Orchestra. ‘Beside its merits as a composition,’ the critic of The Times said of the work, ‘it contains an extremely effective solo part, which was played with virtuosity by M. Christian Ferras, … whose beauty of tone in the lyrical passages was matched by the brilliance of his bravura and the impeccable intonation of his double-stopping.’ Ferras repeated the Fricker, adding Chausson’s Poème for good measure, in a Royal Philharmonic Society concert at the new Royal Festival Hall on 4 May the next year, with Rudolf Schwarz and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. A few days later he and Barbizet were at Wigmore Hall, and he returned to London later in the year for the Mendelssohn Concerto. By now he was becoming a favourite in London.

Meanwhile he was building up his career as an international soloist, touring South Africa in 1951 and making his Berlin Philharmonic debut on 18 November that year at the Titania Palast, with the Violin Concerto in a Beethoven programme conducted by Karl Böhm. In 1952 he made the first of a number of tours of South America and back in France, he and Barbizet premiered the First Violin Sonata by Claude Pascal. In 1954 Ferras acquired a Stradivari violin, ‘Le Président’ of 1721, from luthier Etienne Vatelot. On 24 February 1956 he played the Brahms Concerto in Vienna with a conductor who was to have a crucial influence on his career, Herbert von Karajan.

He first appeared in North America with André Cluytens, playing the Mendelssohn Concerto in Montreal on 29 October 1957. His US debut, at Symphony Hall on 7 March 1959 with the Boston Symphony under Charles Munch, seems on paper to have come quite late, yet he was still only 25. Four days later, he and Munch took their interpretation of the Brahms Concerto to Carnegie Hall in New York. ‘His playing has the fire and brilliance of a young man,’ wrote Howard Taubman in The New York Times. ‘If he does not give a note quite the color or accuracy he wants, it is because of impetuosity. His tone is neither sensuous nor dry; it has a texture and muscularity that reflect the Gallic style of violin playing. His grasp of Brahms indicates that his is not a parochial view of music. He sympathizes with the Brahmsian glow and lyricism and manages to convey a personal perception of the concerto.’ Ferras returned to the US in 1962, 1963, 1965, 1967, 1968, 1970 and 1974, usually playing recitals with Barbizet as well as concertos. On his 1965 visit he gave the premiere of his close friend Serge Nigg’s Sonata for solo violin at Carnegie Hall; and on 24 October 1968, to mark the 23rd anniversary of the United Nations, he and the Orchestra de Paris under Serge Baudo performed Chausson and Tchaikovsky in the General Assembly Hall for delegates and their guests.

Ferras had already premiered Nigg’s Violin Concerto in Paris, on 27 May 1960, with Manuel Rosenthal conducting. For his Salzburg Festival debut that year, he chose Alban Berg’s Concerto. He was well suited to this work as well as the composer’s Double Concerto – which he performed with Barbizet – and the concertos by Bach, Mozart (K216, 218 and 219), Beethoven, Paganini (No. 1 in D), Brahms and Sibelius. In addition to the pieces written for him by Elizalde, Pascal, Gyula Bando and Nigg, he played Schoenberg’s Concerto, Jean Martinon’s Second Concerto and Robert de Fragny’s Danubiana. As late as 1971, he kept to the four-movement mutilation of Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole; but for his second recording of it he finally relented and included the Intermezzo.

Christian Ferras would describe playing Mozart’s G major Concerto for Pope John XXIII, at the Vatican on 20 April 1963 with Rudolf Kempe conducting the RAI Rome Orchestra, as one of the great experiences of his life. However, in the years which should have brought his greatest successes, he began to show signs of the depression and alcoholism which would lead to the final catastrophe. From 1963 Barbizet began to withdraw slightly from their duo; and the 1964 contract with DG which should have brought 20 concerto recordings, mostly with Karajan, produced only those in this box. Even so, in 1966 Ferras was doing well enough to buy his second Strad, the ‘Dragonetti-Milanollo’ of 1728.

According to Michel Schwalbé, by then concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, in 1968 Karajan began to lose interest in Ferras because he could not curtail his drinking – he was vainly trying to cure himself, although he did eventually seek medical help – and their final joint concert performance was a Sibelius Concerto during the 1972 Berliner Festwochen. Early in 1975, having arrived in America to start a two-month tour, Ferras was taken to hospital with a reported heart attack. Having recovered, from that year he taught at the Paris Conservatoire – he needed his professor’s salary, as he had apparently run up gambling debts and had been forced to sell one of his Strads. He kept disappointing his London audience: this writer booked to hear him in both the Elgar Concerto and the Walton, which could have been interesting, but on each occasion, Ferras was replaced by Ralph Holmes (who was himself to die tragically, aged 47).

On 9 March 1982 Ferras returned to the concert platform with a new pianist, Alain Lefèvre, claiming that working with Barbizet again would only remind him of his bad habits, yet he and his old duo partner were reunited for a recital on 6 May. His final concert took place at Vichy on 25 August. An autumn tour of the Iberian peninsula with Lefèvre was planned but on 14 September Ferras took his own life by jumping from the window of his Paris apartment.

From the start Ferras was interested in enriching the repertoire and his early Decca records were quite adventurous. Among his first recordings for the British label – and the only one from 1947 to be published, as two short pieces were left on the shelf – was the Concerto by Federico Elizalde. Known as Fred in his popular guise, Elizalde (1907–1979) was a multi-talented musician: bandleader, pianist, conductor, composer and marksman. Born in Manila (where he also died) of Spanish parentage, he studied in Madrid, London and the US. Having tried to please his parents by turning to law, he switched back to music with Bloch’s encouragement and in 1926 began his career as a jazz bandleader in California. He played a major role in establishing jazz in Britain, while again studying law at Cambridge, then in the 1930s concentrated more on classical music. At various times he was based in Manila, Biarritz, Paris and Madrid, where he studied with Falla. In later years he worked as a broadcaster and conductor in Manila but also captained the Philippines shooting team. He wrote his Violin Concerto in 1943, while domiciled in France under the German Occupation. As one might expect, it is an eclectic piece, with a certain amount of Spanish colouring – especially in the first movement – but also showing the influence of Bloch, for instance in the wistful slow movement.

The repertoire of concertos for piano and violin is not large. The two instruments do not exactly help each other, when pitted against an orchestra, and Mozart quickly gave up on his attempt at the conundrum. The youthful Mendelssohn composed a charming Concerto, Berg’s effort was quite convincing and in more modern times Martinů managed the trick twice. The French musician Ivan Semenoff (1917–1972) composed his concise Double Concerto with Ferras and Barbizet in mind and they gave the first performance in 1952 with the composer on the podium, recording it soon after. In one movement, it falls into clearly defined sections, one of which – an unabashed waltz – must have raised some smiles in the concert hall.

The blind Spanish composer Joaquin Rodrigo (1901–1999) is best remembered for his concertos, especially those for guitar. His Concierto de estío (Summer Concerto) for violin dates, like Elizalde’s work, from 1943 and reflects Rodrigo’s skill in scoring. After studies in Valencia with Francisco Antich, he took the well-worn path from Spain to Paris, where he became a pupil of Dukas. Although he left infinitely more music than his master and was much more ‘neo-classical’ in approach, his works always displayed the same polish and sophistication. This sparkling performance, which teamed Ferras with his teacher Enescu, was virtually the first major Rodrigo recording and it has not been surpassed by later attempts.

The Sonata by Claude Debussy was one of three he completed, out of a planned set of six for various combinations, and the last piece he performed in public. In 1916 Gaston Poulet formed a string quartet and Debussy’s G minor was one of the first works studied. When the group played it to the mortally ill composer, he was equivocal in his opinion, but a few days later he asked Poulet to help him with the virtuoso sections of the Sonata. They duly gave the premiere together in Paris on 5 May 1917 and played it again at St. Jean-de-Luz in September, having to encore it. Unusually for Debussy, it is quite orthodox in construction. In the first movement he uses the effect of a musical saw, which he heard at the 1900 World Exhibition. The interpretation of Ferras and Barbizet is nicely poised in the central interlude and pulses with energy in the outer movements.

Gabriel Fauré wrote most of his chamber works in pairs; in the cases of the Piano Quartets and Violin Sonatas, the first one is immediately appealing, with a dewy freshness, while the second is mature and powerful, requiring more hearings to endear it to the listener. The E minor Sonata, begun at Évian in the summer of 1916, was completed the next year in Paris, where it was premiered on 10 November 1917 by the quartet leader Lucien Capet with Alfred Cortot at the piano. The Ferras-Barbizet rendition, distinctive in its youthful urgency, should make more friends for a work of which Fauré lamented: ‘This poor sonata is very seldom played’.

Maurice Ravel, Ferras’s favourite composer along with Debussy, wrote his Tzigane in 1924 for the Hungarian-born violinist Jelly d’Arányi, in a conscious attempt to produce a show-stopping virtuoso piece. It is Hungarian gipsy music seen through the prism of a refined French sensibility. Although Ravel always had a yen for central and Eastern European music, on this occasion he bit off more than he could easily chew. While composing the Tzigane he got his friend Hélène Jourdan-Morhange to play Paganini Caprices to him and he succeeded admirably in the end. But d’Arányi received the score only three days before she gave the premiere in London on 26 April, with Henri Gil-Marchex at the piano and Ravel in the audience. She had a success, all the same, and Ravel himself later played the piece on tour with Zino Francescatti. The orchestral version was prepared during the summer and given its French premiere by d’Arányi, Samuel Dushkin having already performed it in Amsterdam. Ferras has no difficulty in capturing its authentic brio and his is one of the best interpretations on record, virile in the long opening solo, incisive and exhilarating in the fireworks. He is heard on CD4 in the orchestral version, with the Hungarian-born conductor Georges Sébastian (1903-1989), a Paris Opéra stalwart who brings an authentic touch to the performance. On CD6 Ferras is partnered by Barbizet (Ravel originally specified a piano with the then-new luthéal attachment, which offered several extra registers including a cymbalom effect, but most pianists have employed an ordinary instrument). Strangely, Ferras appears not to have played Ravel’s sonatas involving the violin.

The Poème is the best-known work by Ernest Chausson, a composer who, at the height of his powers, died in a bicycling accident. He wrote it after hearing a Poème elégiaque by the Belgian violinist and composer Eugène Ysaÿe, who accepted the dedication, premiered it at Nancy on 27 November 1896, with Guy Ropartz conducting, and edited it for publication. Hearing Ysaÿe’s own work, it is clear that Chausson borrowed more than just the title for his own piece; but because he was a genius, he made gold out of Ysaÿe’s silver. Sadly Ysaÿe never recorded the Poème but one who did was Enescu, who had often heard him play it; and Ferras carried on the tradition. Whereas Enescu had to make do with a piano accompaniment, Ferras here has the assistance of an orchestra in creating the right brooding atmosphere. Again Sébastian is the conductor.

The most unusual work among the Deccas is the neglected 1940 solo Sonata by Arthur Honegger, a somewhat austere Bach-influenced suite which unites the memories of Neveu and Ferras – she provided the fingerings for the published edition, he gave the first performance in 1948. The composer was present at the premiere and introduced the fifteen-year-old Ferras as ‘one of France’s greatest violinists’. Five years later, Ferras is right inside the music, making it his own. His burnished tone glows in the slower music, while in the faster sections his rhythmic control is absolute. It is a fine example of a ‘creator’s record’.

Like Neveu, Ferras was a player of considerable power, who could generally make himself heard above an orchestra. His May 1954 recording of the Brahms Concerto also shows, however, how lyrically he could spin out the musical line. Working with the Vienna Philharmonic, then as now the world’s finest Brahmsian ensemble, the distinguished German conductor Carl Schuricht (1880–1967) provides a thoughtful framework in the first movement for Ferras – who as usual opts for the Kreisler cadenza rather than the Joachim. (An earlier nine-day session, also in April 1954, included a taping of the composer’s German Requiem with Lisa Della Casa and Heinz Rehfuss, but it was not completed and sadly, the tapes do not seem to exist.) In his later recording with Karajan, Ferras perhaps kept a firmer grip on this mighty movement but it is wonderful to hear him in such an expansive mood. The Adagio is the highlight, with the Viennese oboist setting the scene for a rapturous meditation of depth and what Keats called ‘full-throated ease’. The finale is sturdy and powerful, with the soloist making every note and double-stop tell.

The lovely Mozart concerto performances, from October of the same year, find Ferras matched with another German maestro, Karl Münchinger (1915–1990), and the fine chamber orchestra which he founded in 1945 – conductor and ensemble made innumerable records for Decca. Glowingly played and stylistically impeccable, the interpretation of the G major Concerto, K. 216, was the highlight of the original LP, with Ferras compiling the cadenzas from several sources. Its coupling, the spurious ‘Mozart Violin Concerto No. 6’ – really by Johann Friedrich Eck – received a lot of attention from French violinists: among the others were Thibaud and Janine Andrade. Ferras gives it his usual dedicated attention although he does not play a cadenza. The 1954 recording was made in both mono (with engineer Gil Went) and stereo (with Roy Wallace). The stereo tapes were issued on LP on Decca’s Eclipse imprint (ECS 697) and here receive their first release on CD. The two Mozart Sonatas with Barbizet are delightful and leave the listener wishing for more.

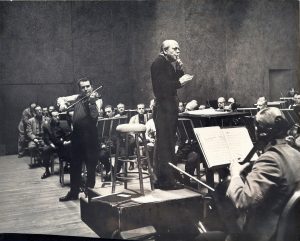

Ferras left us a number of souvenirs of his skill as a Bach player, although he did not set down his thoughts on the solo Sonatas and Partitas until 1977, on an obscure label. From 1953 come Bach’s E major Sonata, BWV 1016, with Marcel Chailley’s widow Céliny Chailley-Richez playing the piano in fine style, and the two ‘Triple Concertos’, the Fifth Brandenburg in D major, BWV 1050, and BWV 1044 in A minor, in gloriously old-fashioned performances with Chailley-Richez at the piano, Jean-Pierre Rampal on flute and Ferras’s mentor Enescu conducting an ensemble whose long-winded appellation puts even The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in the shade. The 1966 Violin Concertos with Karajan are still more anachronistic, when one considers that they come from 13 years later, and the D minor Double Concerto with Schwalbé – though ‘warm-hearted’, as one critic put it – is no match for the celebrated version of seven years earlier with Menuhin.

Of the other concertos with Karajan, the pick has to be the Brahms. Like another Latin player, Gioconda De Vito, Ferras used this concerto for many important debuts and he was fully in command of its difficulties by the time the DG recording was made, dovetailing well with his imperious conductor. The oboe soloist was probably Lothar Koch. The Beethoven and Sibelius are good examples of the high-gloss, high-tension Karajan manner and are very well played by the soloist but the Tchaikovsky, for all its accomplishment, has the Ferras enthusiast looking back yearningly to a more galvanic 1957 recording with Silvestri. Incidentally, as in the Brahms, Ferras always favoured Kreisler’s in the Beethoven Concerto. The Nigg Concerto, with Charles Bruck in charge of the Orchestre Philharmonique of French Radio, is one of those works which manage to sound modern while giving the soloist many opportunities for lyrical flights and ruminative moments. It appears here with its original LP coupling, the 24 Préludes for orchestra by Marius Constant, written as one continuously evolving whole rather than in 24 distinct sections.

The DG recordings with Barbizet are valuable for their intrinsic qualities but also because Ferras did not otherwise record the Lekeu Sonata, the first two by Brahms or any of the Schumann works (although there is a splendid 1959 radio tape of the Schumann D minor). Franck’s Sonata, a wedding present for Ysaÿe, is beautifully laid out and the sizeable work by his shortlived student Lekeu (1871–1894), also dedicated to Ysaÿe and first played by him, does not seem a note too long, so complete is the players’ identification with the music. The interpretations of Brahms’s Sonatas and ‘F-A-E’ Scherzo (the composer’s contribution to a composite sonata written for Joseph Joachim and taking his motto ‘Frei aber einsam’ [Free but lonely] as its cue) have been much admired and in the CD era all four pieces have fitted nicely on to one disc.

Perhaps the most valuable performances with Barbizet are those of Schumann’s first two Sonatas, as few top-drawer artists have followed the lead of the Busch/Serkin duo (who left recordings of both) and Enescu (who recorded the D minor with Chailley-Richez). The Sonatas make as much of a contrast as those by Fauré: the A minor, written at white heat in a few days, is mainly lyrical, with a central Allegretto combining scherzo and slow movement, while the D minor is dramatic with lyrical interludes, such as the Trio of the ‘Sehr lebhaft’ scherzo and the variation third movement, marked ‘Leise, einfach’. The scherzo ends with a Bach chorale and the following variations start unusually, with the theme in triple-stopped pizzicati. Later this remarkable movement refers back to the scherzo. The finale, in sonata form, produces what Joachim called ‘waves of sound’, especially in this rendering, and ends with a substantial D major coda. The lovely Three Romances, Op. 94, were conceived for oboe and piano but Schumann envisaged various other instruments replacing the oboe and many violinists have commandeered them

This conspectus of Christian Ferras’s work for Decca and DG includes a number of short pieces which are all beautifully polished and faithfully presented. A century or more ago, such morsels formed part of every celebrity violin recital, in which the star fiddler would appear with an accompanist; but the Busch-Serkin duo in particular played a major role in establishing the sonata evening as the norm, and by Ferras’s time the sweetmeats had been relegated to encore status. In 1968 he recorded a whole LP programme of these encores with the accompanist Jean-Claude Ambrosini, including half a dozen of Kreisler’s original compositions or transcriptions; and on a visit to Japan in 1971 he set down a further LP’s worth with Shuku Iwasaki. The two sequences make a wonderfully relaxing coda to this important anthology.

Tully Potter