By Alan Sanders

From the early 1920s onwards, English-speaking purchasers of classical records will almost certainly have come across discs played by the ‘Berlin State Opera Orchestra’. This body was clearly a frequent visitor to the recording studios at the time, and it seemingly had no exclusive contract with any company, since it appeared on HMV, Parlophone, Polydor and other labels. It seemed puzzling to some that a pit orchestra should emerge to visit recording studios so frequently, and that it made records under some of the most prestigious German conductors of the time.

‘Berlin State Opera Orchestra’ was in fact a somewhat belittling misnomer, born of the then British fashion of translating foreign titles into the native tongue. The orchestra was in fact that of the Berlin Staatskapelle, and it was and remains the second most prestigious concert-giving body in Berlin after the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (or Berliner Philharmoniker, to give the correct German title).

The Staatskapelle is a much older body than the Philharmoniker, though its present title came much later: its roots go back to the sixteenth century when it was a court orchestra functioning under royal patronage. Then in 1742 Frederick the Great built a fine new opera house situated on the Unter der Linden boulevard in central Berlin, and created a new royal company, the Königliche Oper. From then on the orchestra had a dual existence as a concert-giving body and as an opera orchestra, still under the control of the Prussian Royal Family.

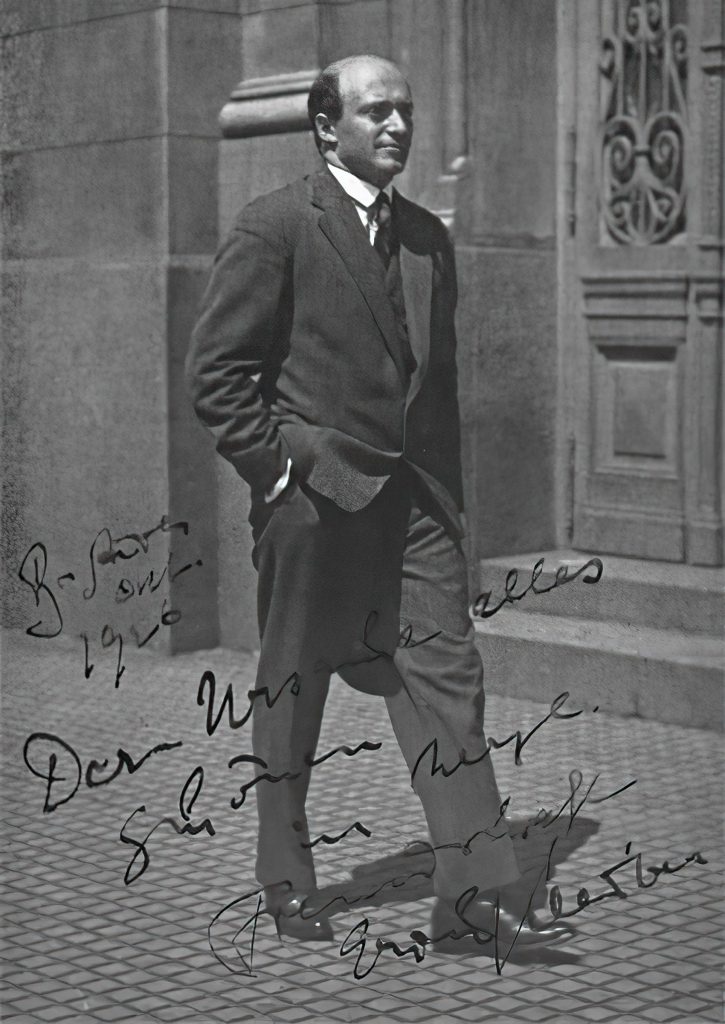

This remained the case until the German Empire and Kingdom of Prussia were abolished in 1918 after the First World War. The opera house and orchestra were thenceforth run by the new Prussian State. Presiding musically over this change was Leo Blech, who had been associated with the house since 1906. In 1923 Blech resigned as music director in order to take over the Deutsches Opernhaus in the Charlottenberg district of Berlin. Various conductors including Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer were approached to take his place, but all refused. The Intendant, Max von Schillings, himself a composer and an able conductor, then proposed that Erich Kleiber be made music director, and so it came to pass. Kleiber was then 33 years old and had only just made his debut in the house as guest conductor of a single performance of Beethoven’s Fidelio, with one rehearsal. On the strength of that experience Von Schillings was convinced that he had the right man.

Up until then Kleiber had enjoyed a rapidly accelerating career. Born in Vienna on 5 August 1890, his childhood was blighted firstly by the death of his father, a Doctor of Philosophy and language teacher, when he was just five years old, and then by the death of his grief-stricken mother less than a year later. Erich and his elder sister were then taken in by their paternal grandfather, who lived in Prague, but he too died a year later, and then it was back to Vienna for the two children to live with an aunt. Erich was not particularly precocious either musically or in his school lessons, but his musical imagination was fired when he heard an orchestra for the first time (Lortzing’s Der Waffenschmied at the Volksoper) and still more so when he heard Mahler conduct his Sixth Symphony in the Grosser Musikvereinsaal. After this overwhelming experience Erich decided that he too must become a conductor, and through following operatic and orchestral performances with the aid of such scores as he could lay his hands on, he gained a good knowledge of basic repertoire.

PHOTO: TULLY POTTER COLLECTION

Having been to a certain extent self-taught Erich was scarcely qualified to enter a school of music, but his relatives were persuaded to let him return to Prague and study at the University while preparing for his Conservatoire entrance examination. Having gained entry to the Conservatoire he was frustrated by the formality of its teaching, though he took advantage of the opportunity to master the Czech language.

Kleiber thus gained a double musical pedigree, one that was later to serve him well when he conducted classical Viennese and waltz music and as well as Czech repertoire. He developed a particular interest in operas of Janáček, and what he described as their ‘inexhaustible fund of dramatic, melodic curves of speech’.

He persuaded a clarinettist friend to smuggle him into rehearsals at the Deutsches Landestheater in Prague. One day he was discovered by the Intendant, Angelo Neumann, and somehow managed to persuade the great man to let him work as an unpaid musical assistant (Neumann died later in that year of 1910). His readiness to lend a hand to any musical activity soon made him known to all. Within months he was directing chorus rehearsals and coaching singers in minor parts. He had studied the violin, but was also a serviceable pianist, and he made his first public appearance as an accompanist to the great American tenor Alfred Piccaver. Then he was noticed by Paul Egar, the newly appointed Intendant of the Darmstadt Court Opera, who invited him to direct the stage music for Johann Nestroy’s comedy Einen Jux will er sich machen. And so, on 1 October 1911, Kleiber made his public debut as a conductor. Five months later he conducted a new production of Hervé’s operetta Mam’zelle Nitouche. After this Egar offered him a three-year contract as third conductor at Darmstadt.

Kleiber remained at Darmstadt for seven seasons. The opera house was blessed by the close but benevolent control of the Grand-Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse, who was very musical. As was normal for a junior house conductor Kleiber was initially given operetta repertoire and made his debut in a new production of Offenbach’s La belle Hélène (sung in German as Die schöne Helena). This was in September 1912. Kleiber was just 22 years old. Highlights of his generally happy time at Darmstadt were visits by the great conductor Arthur Nikisch, whose direction of Tristan und Isolde in particular made an enormous impression.

As time went by Kleiber was given more large-scale operatic fare to conduct, beginning with Der Rosenkavalier in April 1916, which he took over at very short notice. Two years later Nikisch wrote to congratulate Kleiber on his appointment as first conductor of the State Opera at Barmen-Elberfeld (the town was renamed in 1930 as Wuppertal). This was a tougher assignment for him, but his struggles to improve performing standards were successful. After two years, in July 1921, he became first conductor at Düsseldorf, where he showed his interest in contemporary music, arranging concert performances of Schoenberg’s Kammersymphonie No. 1 and Pierrot Lunaire, and an all-Hindemith program.

After less than a year, in May 1922, he moved to Mannheim, where he was musical director of the Opera and also of the Akademie concert series. As well as standard operatic repertoire he gave what is thought to be the first German performances of Stravinsky’s Le Rossignol.

This, then, was Kleiber’s background of experience when he took over the Berlin State Opera as music director in September 1923. He had been well prepared for his new role, but it was a gargantuan initial task, for in his first five weeks he took over eight major productions and insisted on their re-preparation. He enjoyed the firm support of Von Schillings, but Fritz Stiedry, the existing Erster Kapellmeister under Leo Blech, had been passed over, and this fuelled fierce press opposition to the younger man’s appointment. As time went on this receded, but Kleiber always had his critics in Berlin.

On 19 November he conducted his first concert in Vienna, an all-Beethoven program with Walter Gieseking playing the Fourth Concerto, and at about the same time he undertook his first recordings. These were made for a company called Vox (not to be confused with the later American company of that name). The technique of recording electrically via a microphone had not yet been developed commercially, so orchestral recordings were then made by the existing and primitive acoustic process, whereby sound had to be directed into a single large horn by a much reduced body of players, the horn’s vibrations being converted into wave forms inscribed by a stylus onto revolving wax discs.

Kleiber always said that he disliked making records and felt that they were a poor substitute for live music-making. A recording, he said, ‘fixes forever a certain performance, a unique emotional moment, when really no two musical performances are ever the same. If I want to eat asparagus, I’ll try to get fresh ones, and if I cannot get them, then I’ll eat canned asparagus. A record is that, canned music.’ But a certain ambiguity of attitude might be discerned in a remark Kleiber to his sister about his early records: ‘Imagine, you’ll be able to hear me when I’m not there’.

Kleiber made about 40 record sides for Vox with the Staatskapelle orchestra between 1923 and 1927. Initially he had to endure the restrictions of acoustic recording, but his later Vox recordings were made electrically. The company went bankrupt in 1929, but by then Kleiber had moved on.

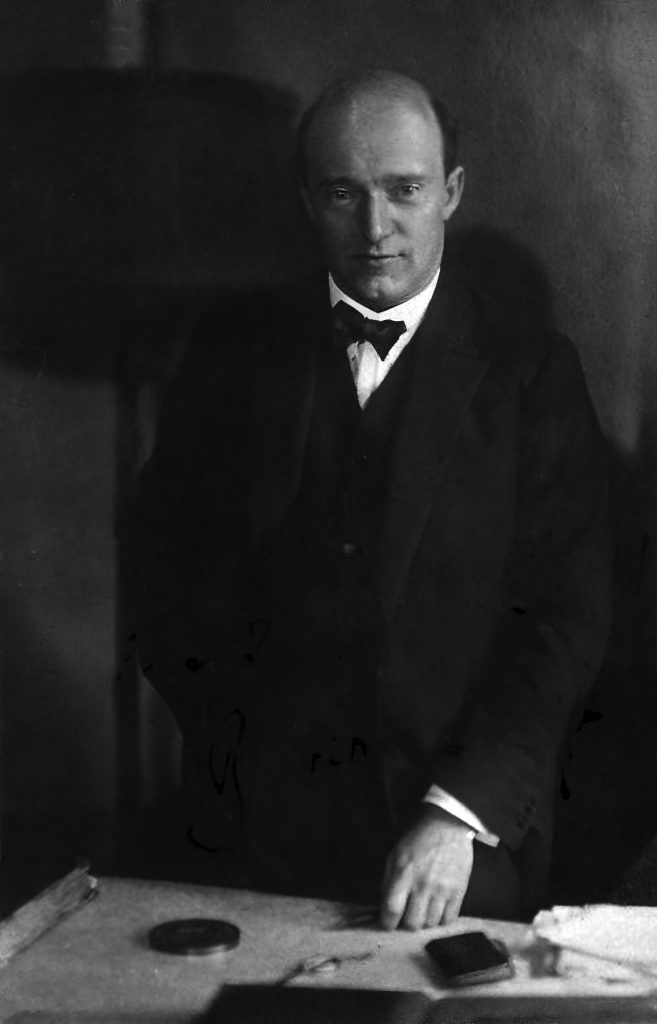

PHOTO: TULLY POTTER COLLECTION

Meanwhile his career at the opera house was flourishing, one of the highlights being the first ever production of Berg’s opera Wozzeck in December 1925. This was by no means Kleiber’s only foray into contemporary or out of the way repertoire. He promoted the premiere production of Milhaud’s opera Christophe Colomb in 1930, and his Staatsoper concerts contained Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, Berg’s Der Wein, and also works by Spohr, Joachim, Roussel, Albéniz, Leopold Mozart and Busoni, to give just a few examples. His inclusion of three satirical pieces by Lord Berners (the same program also contained music by Purcell) caused a particular upset amongst audience members and critics.

Quite naturally none of this adventurous repertoire found its way onto Kleiber’s commercial recordings, which after the Vox period and until early 1929 were made for Deutsche Grammophon. Before the First World War, Grammophon had been an associate of The Gramophone Company, whose records appeared in the UK on the His Master’s Voice label. After the split Grammophon used the name Polydor for its export product.

As a long-established company Grammophon had a number of prominent German conductors on its roster. These included Wilhelm Furtwängler (with the Berlin Philharmonic, of which he was chief conductor), Richard Strauss, Hans Knappertsbusch, Hans Pfitzner, Otto Klemperer and Oskar Fried. This meant that Kleiber’s repertoire opportunities were limited – for instance his only contribution to Grammophon’s Beethoven symphony cycle was the Second Symphony. His beloved Mozart was confined to an overture and a collection of German Dances, for which he had a special affection and of which he performed a selection each year on or near his wife’s birthday: he called them the ‘birthday dances’. Quite unusually, Kleiber programmed a complete cycle of Schubert symphonies in his Staatskapelle concerts, and just one of these, the ‘Unfinished’, is represented in his Grammophon recordings. Mendelssohn’s music would soon be banned when the Nazis came to power, but for the moment his Midsummer Night’s Dream music was acceptable and popular. The Czech side of Kleiber’s heritage was represented in works by Smetana’s ‘Vltava’ and Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony.

Together with a Strauss overture, and a sample each of Viennese, French and Italian overtures, Kleiber’s recorded repertoire for Grammophon can be said to be a fair representation of his sympathies in the realm of mainstream repertoire, if not of his range of interests as a whole. The records were made with the Berlin Philharmonic as well as with his own orchestra: he had made his concert debut with the Philharmonic in the spring on 1924. He was fortunate that despite the deterioration of the economy and rapidly accelerating financial inflation, the late 1920s were a golden period of recording in Germany, the year of 1929 in particular seeing a climax of activity. But the great worldwide economic depression soon affected the classical recording industry very severely.

This set contains a complete collection all of Kleiber’s recordings for the Grammophon company for the first time in any format, including both the rare 1927 version of ‘Vltava’ from Smetana’s Ma vlast and the more familiar remake that replaced it a year later. After severing his association with Grammophon Kleiber made a few recordings for HMV and Odeon and then entered into an association with the Ultraphon company and its corporate successor Telefunken.

Kleiber’s twelve-year span at the Staatsoper represents the most settled period of his career, but the end was traumatic. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, their malign interest in the arts became increasingly intrusive. Many instances of this affected Kleiber’s work, but specific opposition to the production of a new opera, Lulu, by his close friend Alban Berg caused Kleiber to resign his Staatskapelle post. He left Germany in January 1935 and never lived in the country again.

He had already made one visit to South America. Though the continent was a world away from his background culturally, its predominantly Latino lifestyle seemed to suit him, and the opportunity to work with and develop opera houses and orchestras appealed to him. He was still active in free Europe until the Nazi invasion of Austria in 1938, but then decided to move to South America permanently, eventually taking Argentinian citizenship. He did not return to Europe until 1948. His work at the Royal Opera House in London was particularly admired and he also enjoyed success in other continental centres, but as before he was shunned by his native Vienna. ‘People ask me,’ he said, ‘why I never conduct in Vienna. The answer’s quite simple: because I come from there.’

After the war Kleiber recorded exclusively for Decca, and it is ironic that four of his important and best-known post-war recordings, of Le nozze di Figaro, Der Rosenkavalier and Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ and Ninth symphonies, were all recorded at Vienna’s Musikverein with the Wiener Philharmoniker. Kleiber was well remembered in Berlin, however, and in 1954 he accepted an invitation to return to his old post at the Staatsoper when the reconstruction of the bombed opera house was completed. The notion of helping to restore the theatre’s old glories attracted him, but once again there was political interference, this time by East German communist authorities. He resigned in March 1955 before the reopening: the stress of this affair is said to have contributed to his sudden death on 27 January 1956.

He was then 65 years old and was scheduled to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Mozart’s birth, go on a tour of America and make more recordings. But he died on the actual day of the anniversary. A life of continuing achievement and busy activity had been abruptly snuffed out.

| Erich Kleiber – The Complete Polydor 78s is released on Eloquence on 9 April 2021. |