95-year-old piano legend Ruth Slenczynska reminiscences with Eloquence Classics about studying with her legendary mentors, Josef Hofmann and Sergei Rachmaninov, and witnessing the creation of her classmate Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings.

ON MEETING JOSEF HOFMANN FOR THE FIRST TIME

You want to know about Mr Hofmann? Well, I’ll tell you how I first met him. I had at that time [around 1929], the most prominent teacher of piano in the area. This was Berkeley, California, and her name was Alma Schmidt Kennedy. And she was reputedly a student of [Theodor] Leschetizky, hence the great background. And I am willing to believe it, because she gave me a very good start in scales and in arpeggios, and also in harmony. She taught me the names of the chords, and she was very patient lady and a very nice lady. And she wanted very much to get me under the tutorship of a world-class person.

She eventually wanted for me to go to Europe, so whenever a celebrity came to town, she made sure that I played for that celebrity. And the first of those celebrities was Josef Hofmann. First I was taken to a concert that he performed, and he performed on his program Chopin’s B-flat minor Sonata. And I still can hear in my mind, how that Sonata sounded. It was so fascinating to me. I had never heard any kind of a Funeral March before. And the middle of it that had that delicate legato sound, something quite arresting. And this stayed in my mind. I always wanted to play it like that. When I play it today, I try to play it like my remembrance of Hofmann’s performance. I also remember the movement after the Funeral March, that’s called ‘Wind over the Graves’, and he made it sound eerie. I could hear the wind going through trees. It was quite a wonderful sound, quite a wonderful sound. And this made a huge impression on me.

“When I play it today, I try to play it like my remembrance of Hofmann’s performance.”

So he made a very, very strong impression on me. The idea of meeting him was hers entirely, Mrs Kennedy’s. And she arranged that he listen to one of my programs. At that time, I was four years old. I played in Mills college, and it was a real genuine program, and not by any means my first. I had played a couple of little programs before that in other halls, but this Mills College program was my first professional concert, because people bought tickets to hear me. I didn’t know the difference at that time, but now I am aware of that. In fact, on the back of my program, they featured an ad for Steinway pianos, and it said, “Baby Ruth has wisely chosen the Steinway as her instrument,” which I thought was kind of amazing, because I would play naturally on any piano that was put in front of me. So I was kind of lucky to have a good Steinway to play on for that first public recital.

I was overawed by the size of the instrument, of course, because I had never played on a real genuine concert grand before. Always on uprights or on smaller grands, but never a nine foot concert grand. But it was an interesting experience because the base was so strong, and yet when I played a chromatic scale all the way from the bottom to the top of the keyboard, I noticed that it was all in proportion and even, and I was thoroughly entranced with experimenting with this.

In any case, the concert went by and I do remember that afterward, I was told Mr Hofmann was there and by golly, I met him! And it was quite fascinating to me. I liked him right away. You know, he was a father figure and he was the person that I recognized from having played this magnificent Funeral March that I remember.

And then I visited him in his hotel room, and he wanted to see if I really knew harmony as Mrs Kennedy said I did. And he asked me to play various cords for him and various scales for him, which I did. And apparently he was satisfied, because he invited my father and me to come to Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. And of course, this was Mrs Kennedy’s dream. She thought that this would be the most marvelous place for me to go and study.

ON LESSONS WITH AND WITHOUT JOSEF HOFMANN

Now, remember I was barely five years old at that time. I had played my recital when I was four. And it took several months before the negotiations for me to go [to Curtis Institute] were made. Apparently, an apartment was rented for us to occupy, and there was a grand piano in it. And my father believed in nine hours a day of practice even then. He got me up at six and made me practice, and apparently the neighbors complained.

Mr Hofmann’s wife came with the premise, maybe if she has to practice so hard, she isn’t the great genius that you say she is. And of course my father tossed that idea out immediately. Didn’t even think about it twice, or once. But in any case, I went to Mr Hofmann’s house for lessons, and he was, in this role, quite marvelous. I remember he asked me to play scales, but he asked me one hand alone and the other hand alone. And I was so proud of being able to play both hands together. And he would say, “Your left hand is poor. Your left hand is not nearly as good as your right hand.” He said, “Your left hand is a passenger. Your right hand is playing and the left hand is hanging on. It isn’t playing on its own.” And I realized this when he made me do scales with the left hand alone, and was quite insistent on my hand was too weak. Well, it was. I was five years old, so of course I didn’t have a very strong hand! And he wanted there to be a roof, as he said, when your hand is on the piano. The knuckles should form like a roof over your hand. It shouldn’t be down low. So, in any case, he had to see me do scales in the way that he liked scales to be done. And he wanted his scales to start softly and to make an uninterrupted crescendo, all the way to the top, and an uninterrupted decrescendo all the way to the bottom. And this was exceedingly difficult for me to do, because no matter how I tried, there’d be a little accent here, a little accent there. “I can hear wherever you play the thumb,” he would say, or “Wherever you play the third finger. You don’t have control over your hand, particularly the left hand.”

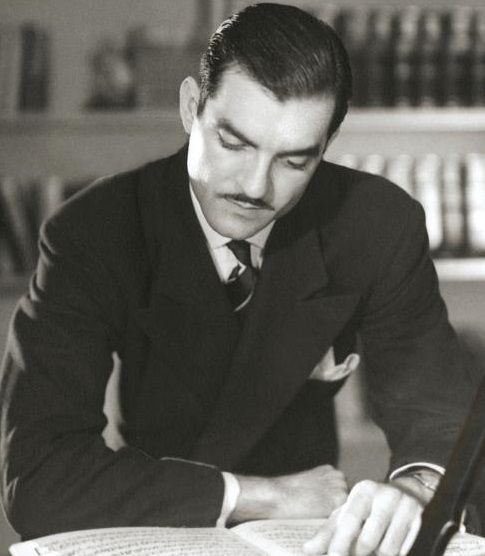

Well at one point, Mr Hofmann had to go away and play concerts. And so when he went away, then I couldn’t take lessons from him. And so he recommended that I go to the Curtis Institute and take lessons from a lady called Isabelle Vengerova. And I had only heard about her from the other students, kind of rumours. People were afraid of this woman. Well, she immediately put me into a technique class, and all the members of the class who were just piano students, as I was, were people who eventually became quite famous. There was Jorge Bolet, and it was Shura Cherkassky, and Abbey Simon. But the boys were all much better than I was, with the exception of one. This boy we called ‘The Pen Pusher’, because he was a composition student and also a voice major, who took piano techniques only incidentally to back up his other studies. And his name was Samuel Barber. Wonderful boy.

ON BEING SAMUEL BARBER’S CLASSMATE AND THE BIRTH OF HIS ADAGIO FOR STRINGS

We all knew that he was so special. He was more than the rest of us combined. We felt it, we knew it, but he couldn’t perform on the piano. He was inept. But of course, you know, if somebody else had been inept, we would have been eager to show our prowess, how much better we could do. But never with Sam somehow. We thought that let him be inept. He’s got something more than we have. He has more than we can do. We can’t compose original music. This boy can. Of course he was great big boy. I was little tiny. But when you’re a little tiny like me and you play the piano, you think that you’re a pianist. All these other kids were pianists regardless of their size, of their age. And of course the others, and even Sam Barber, we remained friends for as long as we lived. And the stories that I can tell you about Samuel Barber are particularly wonderful, because everybody in the school knew that he was a little bit more than just the average good music student. He was a person who was under the tutelage of Fritz Reiner, and people shrank when they thought they were going to have to play in front of Fritz Reiner. Fritz Reiner was our orchestra conductor, and he could slash you to little bits, tongue lashing. He was really terrible. And this poor kid was under his special tutelage. We all felt sorry for him. It was terrible.

One day Fritz Reiner gave an assignment to all the kids who he taught, to write a string quartet. And of course, Sam Barber wrote a string quartet. And he naturally played little bits of it for us in class: the theme from the first movement, second theme from the first movement. We were in awe, because none of us had the imagination to write like this. Sam Barber was special. And then when he finally presented it in class to Mr Reiner, we were all, “What did he say? What did he say?” And Mr Reiner said, “You can throw it all out with the exception of the second movement, but that has possibilities.” He said, “Why don’t you enlarge this, and why don’t you try to orchestrate this? It really is more than a string quartet should do. Orchestrate it, bring in a few more instruments, make it bigger.” And of course this to Sam Barber was, “Ah, I’ve succeeded. I can do this.”

And so he worked on it and worked on it and he wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote. And he wrote all the instruments down that he wanted in it. And it was considered by Mr Reiner good enough to play at the school concert. And this was a great big triumph for Sam. And we all thought he was a genius of some kind. We said “Why don’t you send it out to orchestra conductors, to orchestras all over?” And you know, in those days, there was nobody that you could get to write music for you. You had to do it yourself painstakingly by hand on music paper. And he would stay up all night long, just writing parts for this second movement that he had enlarged. And then he had complete set and he sent this off. He was told he should start at the top. And he certainly did. He sent it to Arturo Toscanini, who at that time was conducting the NBC symphony, most revered orchestra in the country. And of course we asked, “Did you hear from him? Did you hear from him?” Every week. Every month. No.

Well at one point he wrote to Toscanini and said, “Obviously you’re not interested in my composition. And since it is so difficult and costly to hire somebody to write out parts, please send them back to me.” And he got an immediate answer. “How can I send you back your score? I’m going to program it in December!” And the whole school was in an uproar. We were all in an uproar. This was the Adagio for Strings. And to have been present there at the beginning, I think was one of the most exciting things in my whole life.

ON THE PRACTICE HABITS OF SERGEI RACHMANINOV

When I was nine or ten years old, I had the privilege of having nine lessons under Sergei Rachmaninov, and of course Mr Rachmaninov was a great believer in hard work, always telling me I didn’t work hard enough. As if anybody could tell my father that I needed to work harder! He had me up by 6:00 AM and had me working all day, had me working in order to earn my breakfast, and then in order to earn my lunch, and then in order to earn my supper at night, in order to earn my walk, in order to earn the privilege of going to sleep at night. I was always working. And Mr Rachmaninov said about this, “Nine hours a day? Why that’s nothing.” He said, “At one point I worked 17 hours a day.” And I said, “Well, what made you work so hard?” He said he wanted to have a technique that would approach that of Josef Hofmann. And that’s how great Josef Hofmann was revered by one of the titans of the keyboard. Not only that, but by a creative artist. Not just a recreative artist, such as me. So it gave me a lot of respect for the work of Josef Hofmann. Not only was Rachmaninov feeling like that, but almost any pianist thought that the titans of the past were far greater than any of the people that were playing in my era. Josef Hofmann was singular. That’s quite something, to be able to say, “I knew him. I heard him.” I did.

ON PERFOMRING FOR AMERICAN PRESIDENTS

Watch this recent YouTube video of Ruth’s recollections about performing for sitting American Presidents.