Thomas Fine explains the background to the Kubelík Mercury Masters

Sometime immediately before 23 April 1951, two young men boarded a train in New York City and travelled to Chicago carrying a new and technologically ground-breaking microphone. Recording engineers C. Robert (‘Bob’) Fine, 29, and George Piros, 31, arrived at Orchestra Hall the morning of 23 April and began setting up to record the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the baton of its new conductor, Rafael Kubelík, not yet 37 years old at the time.

Fine hung the Neumann U-47 microphone from a rope, about 15 feet above and slightly behind Kubelík’s head as the conductor stood on his podium. The microphone was connected to a high-fidelity dedicated line provided by the local Bell Telephone company, which terminated at Universal Recording Studio, owned by audio pioneer Bill Putnam. The signal was recorded on Putnam’s Ampex model 300 tape machine, on 3M’s Scotch 111 type magnetic tape, at 15 inches per second. Mercury’s Recording Director, David Hall (34 years old), watched the music scores and, working with Kubelík, made sure that satisfactory ‘takes’ of each piece were committed to tape.

The first reel recorded that day was a test of the equipment and connection while the orchestra performed a practice run-through of Ernest Bloch’s Concerto Grosso (heard on CD10 of this set). The master-takes of the piece were subsequently recorded that day (heard on CD2). Based on the audio quality of the master tapes, the phone patch was improved the next day. The result is the lifelike, in-the-room sound of Mussorgsky/Ravel’s Pictures At an Exhibition and Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta.

The Mussorgsky and Bartók were both released in 1951 as Mercury MG 50000 and MG 50001, respectively, under the direction of the label’s young director of classical music Wilma Cozart (24 years old). The Pictures LP received especially positive press, including the description by The New York Times music critic Howard Taubman as ‘the living presence’ of the orchestra. Mercury subsequently adopted Taubman’s description as their classical label name. Fine’s single-microphone recording technique became standard operating procedure for Mercury’s Living Presence recordings throughout the mono LP era.

In November, 1951, Fine and Piros returned the Chicago, this time carrying a massive and heavy Ampex 300 tape machine in its ‘portable’ cases (the size of a steamer trunk). The U-47 mic was connected directly to the tape recorder and on 19 and 20 November, the Chicago Symphony recorded Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s Fourth.

When the Mercury team returned to Chicago in April 1952, Fine drove his new recording truck, a Chevrolet van dubbed the ‘Cinecruiser’ because of its main purpose, recording on-location sound for motion pictures. The van, designed and outfitted at the behest of documentary director Jerome Hill, included new Fairchild tape recorders. During sessions held on 21–22 April that year, the orchestra recorded Tchaikovsky’s ‘Pathétique’ Symphony and Brahms’s First. Unfortunately, only second-generation copy tapes survive for these recordings, with non-optimal sound quality.

The Mercury team, and the recording truck, made another trip to Chicago in 1952, this time in December, a bold late-autumn adventure in those pre-Interstate Highways days. The 4–6 December sessions focused on a Kubelík favourite, Smetana’s Má vlast. Mozart’s Symphony No. 34 was also recorded. Fine again used the Neumann U-47 microphone and Fairchild tape recorder for these recordings. Unfortunately again, only second-generation copy tapes survive for Má vlast and there is audible distortion during some loud passages.

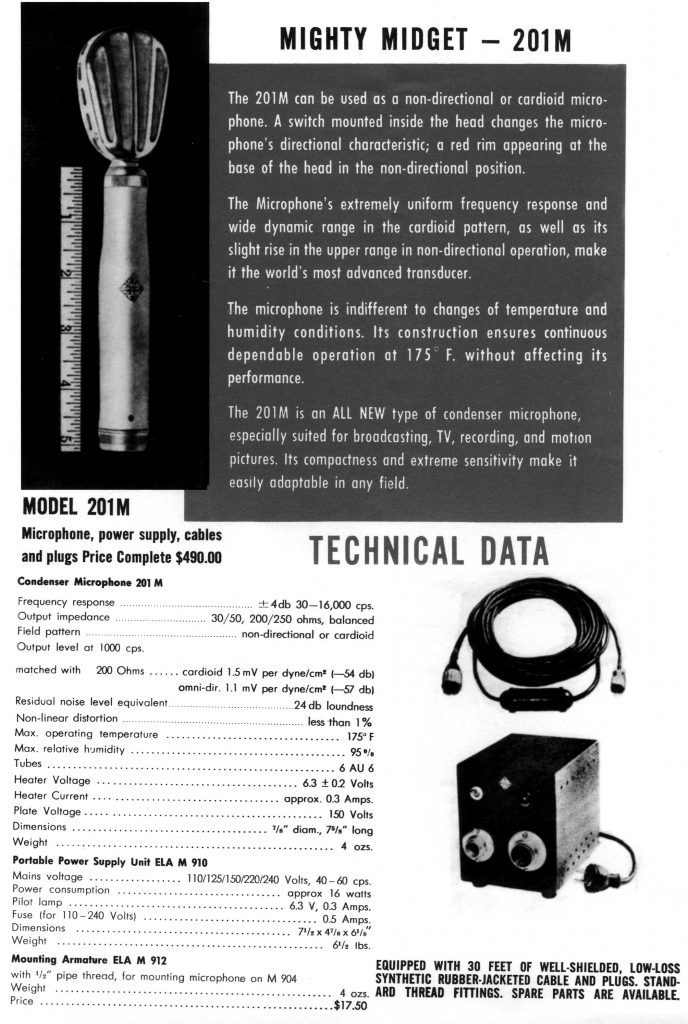

Technical data for the Schoeps M201 microphone

IMAGE: COURTESY THOMAS FINE

For Mercury’s last trip to Chicago to record Rafael Kubelík leading his orchestra, Fine brought along a revolutionary new microphone. The Schoeps M201 offered greater sensitivity and a different frequency-response curve so that it could be placed a bit higher and further out into the hall and still capture all the details of the orchestra, along with more reverberation and ‘room tone,’ resulting in even more life-like recordings. At this last session, on 3–5 April 1953, Kubelík and the Chicago Symphony recorded Mozart’s ‘Prague’ symphony and a program of modernist music: Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis and Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra.

The success of Mercury’s initial 1951 Chicago recordings led the label deeper into the classical music business. Starting in 1952, Mercury began a long recording relationship with the Minneapolis Symphony and conductor Antal Doráti (Mercury’s most prolific recording artist). The next year, Mercury signed a recording contract with the Detroit Symphony and its new conductor, Paul Paray. The single-microphone recording technique pioneered in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall was carried forward in Minneapolis and Detroit, and later with the Halle Orchestra in Manchester, England. Even as stereo recording became the norm, until the mid-1960s, mono LPs released by Mercury Living Presence were made with the single microphone, which also fed the centre channel of Mercury’s three-mic stereo recording technique.

David Hall continued as Recording Director and then Musical Director of Mercury Living Presence until 1956, when he left to pursue a Fulbright Fellowship. George Piros focused on the art of LP mastering and became a disc-cutting legend, retiring in the early 1980s as head of Atlantic Records’ mastering division. Bob Fine and Wilma Cozart married in 1957 and continued to make Mercury Living Presence recordings into the 1960s, including hundreds of pioneering stereo recordings in Minneapolis, Detroit, London, Manchester, Vienna, Milan and even Moscow.

For these seventieth anniversary reissues of the complete Mercury recordings of Rafael Kubelík and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, new high-resolution transfers were made from the best tape sources available. Modern digital audio tools were used to remove phone-line noise from the 1951 recordings and various other problems of early tape recorders and early magnetic tapes, as much as possible without affecting the quality of the music recordings. The recordings were remastered for CD by Thomas Fine, son of the original recording engineer and producer. Tape transfers of all first-generation tapes available were made by Jared Hawkes of Abbey Road Studios.

Experimental Stereo

CD10 in this set contains some rarities and surprises relating to Mercury’s recordings of Rafael Kubelík and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The 1996 interview is with Wilma Cozart Fine, who headed the label’s classical department at the time of the recordings and reissued some of them for CD during her decade as Producer of Mercury Living Presence CDs. Ms. Fine is interviewed by Sedgwick Clark, a former Mercury Records executive who edited booklet copy for all of the original Mercury Living Presence CD reissues. The interview was included on a disc sent to radio stations and press promoting the first mono CD releases. It was recorded at The Mix Place in New York City by John Quinn.

Released here for the first time, is the first reel of Scotch type 111 tape recorded on 23 April 1951, a test recording that captured a rehearsal of Bloch’s Concerto Grosso. All of the work but the first part of the second movement was recorded. The recording includes an announcement by Bob Fine of ‘Bloch Take 1’ and, at the end, Fine instructing the personnel at Bill Putnam’s Universal Recording Studio to reload the tape machine. Thomas Fine transferred the tape to digital and remastered the recording for release.

Bert Whyte in Mercury recording truck, early 1950s

PHOTO: COURTESY THOMAS FINE

The remainder of the recordings are experimental stereo recordings made by Bert Whyte (1920–1994), an audio writer and engineer perhaps best known for his columns in Audio magazine and his role in the founding of, and engineer for Everest Records. During the 1952–53 concert season, Whyte travelled through the American Midwest to make orchestral test recordings using a new staggered-head binaural tape recorder. His first focus was on Leopold Stokowski, whom he recorded in concert with chorus and orchestra at the University of Illinois on 12 November, and at a Detroit Symphony concert the following week (20 November).

Whyte was a friend of Bob Fine and, in the early 1950s, was a seller of audio equipment including Magnecord’s model PT-6 two-channel ‘binaural’ tape recorder. He asked to tag along on Mercury recording trips to make experimental binaural recordings. Bob Fine, who had worked on development of the multi-channel sound system for Cinerama and was himself developing a multi-channel system for cinema-sound (commercialized as PerspectaSound), agreed.

Whyte made recordings at Mercury Chicago sessions in 1952 and 1953. Included on this disc are ‘Tábor’ from Smetana’s Ma vlást recorded on 6 December 1952, and excerpts from Mozart’s ‘Prague’ Symphony recorded on 3 April 1953. On that same day he also recorded portions of the Hindemith Symphonic Metamorphosis.

The different sound perspectives indicate Whyte was experimenting with microphone placement and other recording techniques. The recording of the Smetana work seems to have been done from a more distant perspective than the Mozart. Although it is obviously two-channel (the timpani clearly emanate from the right), it is more difficult to pinpoint the exact locations of other instruments here than on the more closely-recorded Mozart. Evidently, Whyte was experimenting with microphone placement during these sessions. He used a pair of Neumann U-47 microphones, directly feeding his tape machine. The Magnecord tape machine used staggered heads for the two channels, a non-standard format that was obsolete by the mid-1950s. Its primitive transport suffered from audible wow, but the stereo/binaural perspective offers an interesting contrast to the single-mic mono masters.

Whyte’s recordings were never intended for commercial release, and in fact he was ordered by Mercury executives to destroy his tapes, but these various reels survived, eventually making their way to a private collector, who allowed a copy of the Mozart “Prague” excerpts to be made; these reels were transferred to digital by Mark Obert-Thorn. After the collector’s death, the whereabouts of the rest of the original tapes became unknown. The copy of the Smetana work, mislabelled as a Stokowski performance, was sent to Stokowski’s secretary Jack Baumgarten, possibly by Whyte himself. It became part of the collection of the Leopold Stokowski Society in London, and was ultimately given to Obert-Thorn. While other experimental tapes of these sessions may eventually turn up, the ones presented here are all that are currently known to exist.

Thomas Fine owns and operates an audio transfer and mastering studio in Brewster, New York, USA. Since 2013, he has provided consulting and mastering services for various Mercury Living Presence releases. He is the son of C. Robert (Bob) Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine, the original recording engineer and producer of much of the Mercury Living Presence catalogue.